Christian Bale: Freedom Fighter

Christian Bale’s time as the Caped Crusader may have ended, but with The Flowers of War it’s clear he’s still an outsider at heart

This month christian bale finally swoops back onto our screens as Gotham’s rubber-clad avenger in The Dark Knight Rises. It is his third outing as Batman, and his last. Such an iconic role carries with it the danger of pigeonholing an actor, but not Bale. Ever since his breakthrough as a child, in Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun (1987), the 38-year-old Welshman has refused to stand still as an actor. And although he hit the headlines for the wrong reasons when he launched into a sweary (albeit very funny) rant on the set of Terminator Salvation(2009), it is his work that usually gets people talking – and the lengths to which he is sometimes prepared to go for a character. Who wasn’t shocked by his cadaverous appearance in 2004’s The Machinist – a look achieved, famously, by shedding 63 pounds. The man was literally his own special effect. Some thought he should have been at least nominated for an Oscar. Then finally last year, after a string of acclaimed lead performances in films such as American Psycho (2000) and The Prestige (2006), the temperamental perfectionist won one, for his colourful supporting turn in The Fighter (2010).

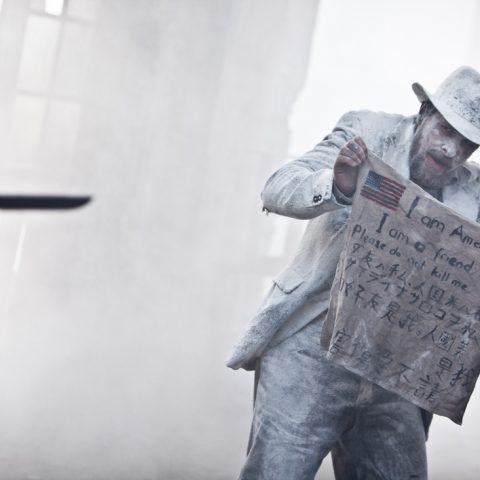

He continues to make adventurous choices, and recently travelled to China to collaborate with director Zhang Yimou (Hero, House of Flying Daggers) on The Flowers of War: an artful and controversial film about the horrific events in 1937 known as the Rape of Nanking. Bale plays John Miller, a self-centred American who slowly finds a cause when he poses as a priest and takes refuge with a group of young women and children in a church.

You were filmed in China getting pushed around by some security guys when you ruffled government feathers in your attempt to visit the activist Chen Guangcheng. What were you trying to achieve?

Ah, well that’s just something that interests me and I think has resonance with this movie. You know, individual spirit versus stronger forces. But, I have to say, with respect to my director, I’d like to keep that as a separate story away from this movie.

Fair enough. The Flowers of War is set four years before the events of Empire of the Sun, and is similarly to do with Japanese occupation. Did you want to revisit the period from an adult’s perspective?

It’s obviously through very different eyes. John Miller is a refugee of the Dust Bowl and somebody who has this tortured past – as anybody who behaves in quite such a clown-like and raucous manner as him, drinking and pursuing excess, does. You know, there’s always something they’re covering up, something behind them – and you couldn’t contrast that more strongly than with Jim Graham from Empire of the Sun.

Do you have strong memories of the earlier film, though?

Of course, but it’s like a whole other lifetime. Also that was an American bubble of a production within China, whereas this was an actual Chinese production, which was a new experience that I wanted to jump into.

You travelled around a lot from very early childhood, and grew up in different places. Does that help you in your work?

It helps immensely because I adapt very quickly. So I’m very comfortable, I’m not unnerved by being in a country like China and being the only person that doesn’t speak the language. I find that amusing. I enjoy it. I assume that’s due to my upbringing, who knows? But, you know, I think people either have a sense of adventure or they don’t.

Is adventure also what you’re looking for in your work?

It is, but you don’t have to travel to foreign countries for that; obviously the main experiences will happen right inside your head. But that’s what you’re looking for, otherwise you’re in a rut. And that’s what audiences are looking for as well. Why would you want to see the same thing rehashed again and again? You want to see people reaching out and trying something different. Obviously sometimes you fall flat on your face, but those are the people I admire, people that make an effort. Sometimes it doesn’t work, but when it works it’s memorable.

The Flowers of War is a story about sacrifice. Have you ever sacrificed something for someone or for a cause?

Absolutely. I think that’s the heart of life, really. I mean you come to understand that immensely as a parent. And even before you become a parent, maybe you’ve got some vague notions about it, maybe it’s a theory. But it becomes practice once you become a parent. And it’s when you come to understand truly – truly – the meaning of being prepared to kill and die for somebody, and something.

So being a father has changed your life?

Absolutely, as it should do. And it enriches it. When you find something, a cause as you call it, a person, or whatever it is that you’re willing to kill or die for, then that becomes the meaning of your life.

You’re clearly enjoying fatherhood.

It’s just the most wonderful thing, and it’s helped me so much. Because you know what? You put aside your bullshit. You have to. You have to recognise all the nonsense, all the crap that you thought was important before, and just say, ‘Get real, man. Get on with life.’ My daughter Emmeline’s still learning humour and she’s the funniest little girl in the world – I’m not being funny about that, she is – and she helped me no end in this role in this movie. Obviously it’s a minor thing, who cares about acting in comparison to being a parent? But, man, it just resonated so much because of having a little girl.

The film has been criticised for showing the Japanese as all bad and the Chinese as all good. How do you respond to that?

I think that the only credible discrepancy that I have been presented with about the Rape of Nanking has nothing to do with actual events occurring, it’s just to do with the numbers. And even at the lowest the numbers are enormous. So to me that makes no difference in terms of the movie that we’re making – atrocious things happened. In wartime moral codes get turned on their heads. In life we’re taught you don’t kill. Soldiers are taught to kill and it’s inevitable that the abnormal becomes normal for somebody, and they start to break other moral codes. It’s terrifyingly consistent throughout the world. So I think there’s no way of avoiding that.

Does it also have to do with who’s telling the story in the film?

Yes, you have to remember that the movie is being told through the eyes of a 13-year-old girl. These are her memories, these are her recollections, some of which are bizarrely beautiful. Inevitably she remembers that there were soldiers that she came in contact with who murdered her friends, raped her friends, and she’s not going to wish to understand their side of the story. And I think that’s important to remember, that this is the memories of a 13-year-old girl who’s seen this. So every character, was he or she exactly like that? Was John Miller like that? I’m not sure. But that’s how she remembers him.

This film is also about heroes. Do you have a personal one?

It always has been and always will be my father. He was a hell of a guy, always entertaining, never boring, and a believer in forging his own path. I had a very interesting childhood growing up with him as my inspiration.

Was it tough finding your own place in life when you have a father who is such a strong figure?

In regards to that, the only discovery I think had to make was that it’s very healthy for all kids to act; but I think it’s desperately unhealthy for kids to act professionally and to find the responsibility that comes with that. It was something that I liked a great deal about the kids in this movie. They’re working with a pre-eminent Chinese director, and they were all extraordinary actors, as most children are, and I would talk to them and say, ‘So, do you want to keep doing this?’ and they would say, ‘God, I never want to make any movies ever again in my life.’ They had this great realism about them. But I would say, ‘You know what? When I was 13 I said, “God, no. I’m not doing this ever again. And look at me now. So watch out!”’

Is it lesson you’ll teach your daughter?

Yeah, she won’t be doing it.

Does she understand what you do?

She gets it. She finds it so boring. She goes for the Kraft services, and then she looks at me and goes, ‘Daddy, you do the same thing again and again.’

Where did you put your Oscar?

My daughter has it. Every time I’ve won anything I walk in the door and she goes, ‘I’ll have that,’ and she takes it from me and she goes and puts it wherever she wants it.

Does being a father affect your choice of roles?

It’s obviously the most meaningful thing in my life so you look at a movie like this and it affected my performance incredibly. It just wouldn’t have been the same performance had I not have been a father at that point. But, you know, we all have multiple sides to us, as we should have, and it doesn’t mean that I’m always going to make movies that my daughter can see. Hey, most of them she’s going to have to see much later.

Is there anything you won’t forget about working in China?

I won’t forget the enjoyment, which I think would not be enjoyable to many people, of the language isolation. Maybe it comes from being a little bit of a loner myself. It didn’t faze me whatsoever. I was quite happy to know what I needed to know. I could watch people and work out what was being said. I learnt to have a shorthand with Yimou. You come to understand people and it kind of goes beyond language. I came to communicate better with Yimou than I have with a lot of English-speaking directors.

Did you learn any Mandarin?

I learnt some. The kids taught me the dirty words and I enjoyed shouting ‘It’s a wrap!’ when it wasn’t.

As a loner do you still find time for yourself?

Absolutely, you always find time for yourself. It doesn’t matter where you are, you can go anywhere you want in your head.

So you don’t have to go on bike rides or hikes, or whatever?

I still enjoy doing that. I have a love for motorcycles.

Finally, The Flowers of War is quite a dark movie and your version of Batman is the darkest yet. Do you think that’s a trend?

I think it’s coming to recognise more accurately the human condition. It’s about saying, ‘Hey, let’s not dumb things down for the audience. Things don’t have to play out like a children’s fairy tale. We’re human. We understand what it’s like to be human. Let’s start telling stories more truthfully’.